This is an archive page; this conference occurred in May 2000.

The mfm homepage is here.

|

|

University of Manchester, 18-20 May 2000

![]()

Markedness in the nasal component

Bert Botma (University of Amsterdam) and Erik Jan van der

Torre (University of Leiden)

Taking as our background the typological generalisations regarding nasal inventories in Ferguson (1975) and Maddieson (1984), we would like to focus in this talk on some cross-linguistically observed markedness relations within the class of nasals. The basic claim that we wish to make is that in a typical three-nasal system like Dutch or English (i.e. one consisting of [m, n, N], where N = velar nasal) three distinct and inherently conflicting types of markedness -- or, for that matter, unmarkedness -- can be observed, each of which corresponds to a particular type of nasal.

1. Consonantal unmarkedness

We argue that [m] is consonantally unmarked, by which we mean that it is the optimal

consonantal, or "stop-like", nasal. Cross-linguistic evidence in favour of this position comes

from syllable phonotactics, resistance to lenition processes, and patterning in segmental co-occurrence effects.

2. Segmental unmarkedness

We argue that [n] is the segmentally unmarked nasal, by which we mean that it is the optimal

segmental realisation of nasality. Evidence in favour of this position comes first and foremost

from the unmarked status of coronal segments in general:

coronals are marked by their distributional freedom, typological frequency and susceptibility to place assimilation, and are

generally the preferred default and epenthetic segments (cf. Paradis & Prunet 1991).

3. Vocalic unmarkedness

We argue that [N] is the vocalically unmarked nasal, by which we mean that it is the most

"vowel-like" nasal. Support from those languages in which [N] has a restricted distribution as

compared to /m/ and /n/, and from those languages in which [N] is the only nasal that is

independently allowed syllable-finally.

Building on Golston & van der Hulst (1999) and Botma & van der Torre (to appear), we provide a formal account of the observed (un)markedness effects within the class of nasals. Our basic claim is that syllables consist of "consonantal" and "vocalic" positions. Material that is syllabified under a nucleus (or rhyme) is typically more vocalic than segments syllabified under an onset. In Botma & van der Torre we claim that prosodic organisation involves top-down and bottom-up requirements, the interaction of which determines the prosodic interpretation of segments.

In this talk we would like to claim that these top-down and bottom-up forces can also be observed in the class of nasals. Thus, the consonantally unmarked nasal /m/ is expected to occur typically in onset positions and, at the same time, is the nasal that is most resistent to weakening effects. The velar nasal on the other hand, being the most vowel-like nasal, is expected to show a cross-linguistic preference for a vocalic position (i.e., under the nucleus). The coronal nasal is the segmentally unmarked nasal and therefore we do not expect strong positional preferences.

References

Anderson, S. (1975). "The description of nasal consonants and internal structure of segments", in Nasálfest, 1-26.

Booij, G. (1995). The Phonology of Dutch. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Booij, G. (1996). "Cliticisation as prosodic integration: the case of Dutch", The Linguistic Review 13, 219-42.

Botma, B. & E.J. van der Torre (to appear). "The prosodic interpretation of sonorants in Dutch", Linguistics in the Netherlands 2000.

Bolognesi, R. (1998). The Phonology of Campidanian Sardinian: A Unitary Account of a Self-Organizing Structure. HIL dissertation. The Hague, Holland Academic Graphics.

Davenport, M. (1995). "Nasality in dependency phonology", in H. van der Hulst & J. van de Weijer (eds.) Leiden in Last (HIL Phonology Papers 1). The Hague, Holland Academic Graphics, 89-103.

Delattre, P. (1965). "La nasalité vocalique en français et anglais", The French Review 39, 92-109.

Ferguson, C. (1975). "Universal tendencies and 'normal' nasality", in Nasálfest, 175-96.

Ferguson, C., L. Hyman & J. Ohala, eds. (1975). Nasálfest: Papers from a Symposium on Nasals and Nasalization, Language Universals Project, University of Stanford.

Foley, J. (1975). "Nasalization as a universal phonological process", in Nasálfest, 197-212.

Golston, C. and H. van der Hulst (1999) 'Stricture is structure.' In B. Hermans and M. van Oostendorp, eds., The Derivational Residue. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Philadelphia, 153-73.

Herbert, R. (1986). Language Universals, Markedness Theory, and Natural Phonetic Processes. Trends in Linguistics, 25. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter.

Ladefoged, P. & I. Maddieson (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

Maddieson, I. (1984). Patterns of Sounds. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Ohala, J. (1975). "Phonetic explanations for nasal sound patterns", in Nasálfest, 289-316.

Paradis, C. & J.F. Prunet (eds.) (1991). The Special Status of Coronals: Internal and External Evidence (Phonology and Phonetics 2). San Diego, Academic Press.

Steriade, D. (1993). "Closure, release, and nasal contours", in Huffman, M. & R. Krakow (eds.) Nasals, Nasalization, and the Velum. San Diego, Academic Press, 401-70.

Trigo, L. (1993). "The inherent structure of nasal segments", in Huffman, M. & R. Krakow (eds.) Nasals, Nasalization, and the Velum. San Diego, Academic Press, 369-400.

Yip, M. (1991). "Coronals, consonant clusters, and the coda condition", in C. Paradis and J.F. Prunet (eds.) The Special Status of Coronals. San Diego, Academic Press Inc., 61-78.

Markedness and alignment

Ellen Broselow (State University of New York at Stony Brook)

A number of languages permit structure types at the right edges of morphological constituents that are not permitted elsewhere. For example, the Central Sulawesi language Balantak tolerates consonant cluster types at stem-suffix boundaries that are not permitted within morphemes or at prefix-stem boundaries. Facts like these have generally been accounted for in various ways: (i) licensing: a final consonant is protected either by being rendered invisible (extrametrical), by being allowed to attach directly to the PWd rather than to the syllable, or by serving as onset to a following (invisible) vowel; or (ii) alignment: a stem-final consonant is protected by the requirement that the right edge of the morphological constituent (the stem) coincide with the right edge of a prosodic constituent (syllable or prosodic word). I will argue that the tolerance of marked clusters at stem-suffix boundaries in Balantak is a result of a high-ranked constraint requiring that the right edge of the stem be aligned with t he right edge of a syllable. This constraint also accounts for the allomorphy of the second person possessive suffix, which is realized variously as a suffix or as an infix. While licensing/extrametricality approaches compete successfully with alignment approaches in accounting for increased tolerance of marked structures at right edges, only the alignment approach can account for the full range of the Balantak data.

References

Busenitz, Robert L. (1994) Marking Focus in Balantak. In R. van den Berg, ed., Studies in Sulawesi Linguistics, Part III, 1-15. NUSA: Linguistic Studies of Indonesian and Other Languages in Indonesia 36.

Busenitz, Robert L. and Marilyn J. Busenitz (1991) Balantak phonology and morphophonemics. In J.J. Sneddon, ed., Studies in Sulawesi Linguistics, Part II, 29-47. NUSA: Linguistic Studies of Indonesian and Other Languages in Indonesia 33.

McCarthy, John and Alan Prince (1993a) Prosodic Morphology I: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction. Ms., University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Rutgers University.

McCarthy, John and Alan Prince (1993b) Generalized alignment. In G. Booij and J. van Marle (eds.) Yearbook of Morphology 1993. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 79-153. Also available from Rutgers Optimality Archive.

Rozali, Latif, Asri Hente, Darwis Mustafa, and Ny. Nurhayati P. (1992) Struktur Bahasa Balantak. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

The foot as a segmental domain

John Harris (University College London)

The coda is widely cited as a prime neutralisation site, one which disfavours the appearance of marked feature specifications. Great play is often made of the claim that the coda subsumes two linearly defined contexts, preconsonantal and word-final. The paper focuses on another pair of contexts which conspire to condition segmental distributions -- word-final and intervocalic.

Extending the coda-based account to this conjunction involves subverting core syllabification by allowing an intervocalic consonant to be captured by the first syllable. In fact there is a simpler available alternative, one which identifies the foot as the unitary context. The conclusion is that the foot, no less than the syllable, is capable of conditioning both segmental and metrical phenomena. One advantage the foot-centred approach enjoys over one based on the coda is that it allows us to unify prosodically sensitive vowel and consonant neutralisation.

If you want to download the full handout (with references) for this paper, please click here (revised version, 16 May 2000). You will need Adobe Acrobat Reader (can be downloaded free) to open the file.

Lenition: the search for a relevant hierarchical

framework

Norval Smith (University of Amsterdam)

There are two sides to the study of lenition--what actually happens to

the lenited segments, and the question of the domain within which this

phenomenon applies. In this talk I will be concerned primarily with the

second part of the question, that concerning the domain.This leads us

directly to the problem of syllable structure.

Over the years, a

number of problems have come to the fore concerning the analysis of

syllable structure. One major problem is concerned with just what aspects

of syllable structure can be considered to be relevant. Different aims

result in different analyses.

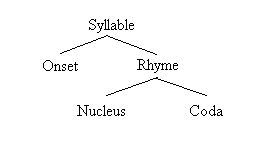

1. On the one hand, we are all familiar with analyses of the syllable where phonotactic considerations are primary. There have been few improvements on the 1000-year old Chinese traditional analysis as:

The present evidence for this model mostly involves the insight that

the more mutual interference elements in the syllable display the more

likely they are to belong to the same constituent. One improvement that

has been introduced into this model, involves the notion of headship. So

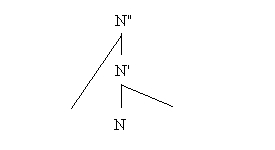

Levin encodes headship in her X'-model:

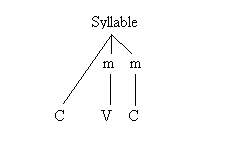

2. If one is dealing with accent systems, however, one might wish to deal in models of the syllable like:

Even if one were to want to recognize a moraic rhyme, then all that would change would be

that we would have a non-moraic constituent (the onset), and a moraic constituent. This latter

would of course be equivalent to the rhyme, but the question of assignment of moras to the

nucleus and the coda is then irrelevant. What is more a coda in a quantity-sensitive stress

language where VC counted as heavy, would have to be treated differently from one where

VC counted as light. No successful integration of moras in a hierarchical model of the syllable

has yet been made.

3. The recognition of the problems connected with the vexed relationship between the phonotactic and the prosodic aspects of the syllable led Van der Hulst (1996) to appeal to the distinction between lexical and postlexical phonology. Van der Hulst posited a distinction between the phonotactic (or logical) syllable with constituent structure, and the prosodic syllable with moraic structure, whereby the last is closer to the phonetics and therefore postlexical.

This does not necessarily offer a solution within an OT approach. While distinct lexical and postlexical levels are not essentially excluded in such a model, problems would remain. For a start the internal syllable structure has to be definable at the postlexical level.

4. There are phonotactic restrictions as to the second consonant in (maximally bisyllabic) morphemes in some languages, such as !Xu with 92 consonants allowed in C1 position and only 4 in C2 position (Snyman 1975), and !Xõo with ca. 115 consonants allowed in C1 position and only 5 in C2 position (Traill 1985). We have no means to express this kind of relationship in any kind of constraining and elegant fashion. The similarities to fortition and lenition in respect of the two consonantal positions are evident.

This kind of consideration may even compel us to recognize two word-sized hierarchical constituents--a Prosodic Phonological Word and a Phonotactic Phonological Word. This may have some relevance for unresolved problems surrounding the Phonological Word, and its relationship to compounding and cliticization.

5. Everett (1997) studies the accent system of Banawá and concludes that Foot boundaries do not always coincide with Syllable boundaries. This is a strong piece of evidence that not one but two hierarchical structures are involved. Everett assumes a constraint-hierarchy for Banawá whereby SyllableIntegrity is dominated by ParseMora(InFoot). In other words Syllables are constructed from Segments, and Feet from Morae. SyllableIntegrity is an alignment constraint stating that Syllables cannot be split between Feet, but the higher ranking assigned to ParseMora(InFoot) in Banawá overrides the effects of this constraint. For most languages SyllableIntegrity will however be ranked above ParseMora(InFoot).

6. Two constraints have been proposed concerning the interrelationship of Syllable Weight and Accent (Prince 1991): WeightToStress (if Heavy then Stressed) and StressToWeight (if Stressed then Heavy). The first stresses heavy syllables, and the second gives an extra mora to stressed syllables. These two constraints differ in a curious fashion in their effects. The first aligns a prosodic prominence structure with a particular syllable type defined in terms of segmental make-up. The segments are, all other things being equal, unaltered--an aligned relationship in terms of syllable and foot structure is established with reference to these segments. The second constraint also involves an aligned relationship in terms of syllable and foot structure, but explicitly involves a change in the segments making up the syllable, such as an increase in vowel length. This constraint is designed to prevent mismatches between the moraic structure and the segmental structure, and ensures this by selecting candidates involving segmental unfaithfulness.

All the foregoing points suggest the necessity of establishing separate accentual and phonotactic hierarchies. In other words we must distinguish two kinds of prominence, often previously conflated--accentual prominence, and sonority prominence. The first defines the head of a Foot, the second the head of a Syllable.

Just as we can identify the most prominent foot in the word--the foot containing the primary accent--so we can identify the most prominent syllable in the word. This the occurrence of lenition phenomena in various languages helps us to do. The obvious candidate is the first syllable in the word. Historical change tend to cause more loss of segments at the righthand edge of the word than at the lefthand edge.

Two types of lenition seem to occur--across-the-board lenition, and accent-related lenition. In both cases the trigger (see Bolognesi 1998 for discussion) seems to be the occurrence of a preceding vowel (not necessarily tautosyllabic). Across-the-board lenition potentially affects every consonant except the onset of the prominent syllable. Accent-related lenition works foot-internally, affecting only intervocalic consonants within feet. This is presumably not without relevance for the fact that the minimal word is normally foot-sized.

The inverse of lenition--fortition--occurs word-initially, or foot-initially (cf. foot-initial fortition in Alutiiq (Leer 1985)). Across-the-board lenition takes no account of accentual patterning, however. The presence of a proclitic article in Sardinian will cause lention to the first onset consonant in the following lexical word (Bolognesi 1998). We can conclude that accent has in principle nothing to do with the occurrence of lenition, although it may get involved.

Across-the-board lenition should not be seen in terms of a sort of harmony. Each non-initial consonant must be examined to see if lenition can take place or not. If lenition does not take place, this does not prevent lenition from occurring in subsequent consonants.

Lenition is seen as the spreading of a V-element from the preceding vowel. This gives rise variously to voicing, continuancy, or both. These are both instantiations of a V-element. In my talk I will examine several proposals for supra-syllabic hierarchical representations of word-structure which make it easier to express the conditions under which lenition occurs.

References

Bolognesi, Roberto (1998) The phonology of Campidanian Sardinian: A unitary account of a self-organizing structure. Leiden: Holland Institute of Generative Linguistics.

Everett, D.L. (1997) "Syllable integrity". WCCFL 16.

Leer, J. (1985) "Prosody in Alutiiq (the Koniag and Chugach dialects of Alaskan Yupik)". In M. Krauss (ed.), Yupik Eskimo prosodic systems: Descriptive and comparative studies. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, 77-134.

Levin, Juliette (1987) "Constraints on syllabification in French: Eliminating truncation rules", in D. Birdsong & J.P. Montreuil (eds.), Advances in Romance linguistics. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Prince, Alan (1990) "Quantitative consequences of rhythmic organization". In M. Ziokowski, M. Noske & K. Deaton (eds.), CLS 26: Volume 2: The Parasession on the Syllable in Phonetics & Phonology. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society, 355-398.

Snyman, J.W. (1975) u'hõasi fonologie en woordeboek. Kaapstad: A. A. Balkema.

Traill, Anthony (1985) Phonetic and phonological studies of !Xóõ Bushman. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Van der Hulst (1996) Structural paradoxes in phonology. [Unpublished paper presented at the HIL OT Workshop, December 1996, Leiden University.]

![]()