The reading material for this week is chapter 12 and sections 14.9 — 14.11 from Fitch (2010). Before you read this, here are some thoughts on the term ‘protolanguage’ that are good to keep in mind.

‘Protolanguage’

The term ‘protolanguage’ is relatively old, but was re-introduced into evolutionary linguistics (and popularised) by Derek Bickerton (1990) (but see section 11.7 in Fitch (2002) for some other references). When he did that, Bickerton had very clear ideas about the position of a supposed protolanguage stage in evolutionary history. It was an intermediate stage in which there was no syntax yet, and words were just put together. The step from protolanguage to full language, according to Bickerton, was one sudden leap. Thus, for Bickerton it was a very straightforward thing to claim that there was one single protolanguage stage: it was at the point in history where multiple words were communicated, but where there was no syntax at all, and there were no other stages in between this stage and ‘full language’.

Other researchers have picked up the term protolanguage, and hypothesised about its properties. But these other researchers are not necessarily proponents of the ‘one huge leap’ hypothesis of syntax (even Bickerton himself has dropped this view in more recent work), and tend to advocate a more gradual trajectory from no language to full language. But then, the place of protolanguage in evolutionary history is not as straightforward as it was, and it seems no longer sensible to speak of *the* protolanguage stage. Should we abandon the concept ‘protolanguage’ altogether, then? Some authors seem to imply this, by calling protolanguage a speculative concept (Bidese et al., 2012). I do not think that such hard measures are necessary, as long as we keep in mind that the term ‘protolanguage’ is more a tool for hypothesising about the emergence of language, than it is literally a point in time in the course of evolution. If this is kept in mind, the term protolanguage can help us formulate clear hypotheses about how language came about:

The protolanguage debate provides a fascinating test case for the development of evolutionary linguistics: it has the notable advantage that the opposing viewpoints are clearly stated, open to scrutiny, and pugnaciously defended. (Smith, 2010)

Thus, different accounts of protolanguage then simply emphasise different processes in the emergence of language. These accounts of protolanguage are not necessarily mutually exclusive. If the possibility is left open that there was more than one protolanguage stage, then one could imagine that there could be truth in more than one of the accounts of protolanguage mentioned here.

About the reading

In chapter 12, Fitch (2010) discusses what he calls lexical protolanguage.

The first half of the chapter discusses accounts of protolanguage that rely on ‘living fossils’ of early human language, and focuses on the work of Derek Bickerton and Ray Jackendoff. These accounts address questions about the <b>structure of language</b> in the language evolution process, but we will see that Fitch connects questions about <b>the function of language</b> to it as well.

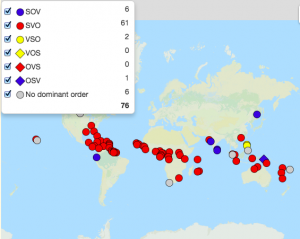

I will discuss Bickerton’s and Jackendoff’s accounts in the lecture, and discuss different kinds of ‘living fossils’. To have a quick look at one of these, pidgin and creole, have a look at APiCS. This website features data from 76 pidgin and creole languages, and describes many of their properties (such as basic word order; see picture).

In the second half, Fitch addresses a problem with protolanguage accounts like those of Bickerton and Jackendoff: they presuppose cooperative information sharing among individuals. Fitch discusses ways to explain its emergence:

- Dunbar’s grooming/gossip account

- Deacon’s account of symbolism

- Fitch’s own 2 stage model of kin selection and reciprocal altruism

This gives us a clear view of different existing positions in the debate about why language, a system that relies on cooperative information sharing, came into existence at all.

At the end of the chapter, Fitch is still left with a question that was central in Bickerton’s and Jackendoff’s work: where does syntax come from? Fitch wisely states that different kinds of answers to this question may not be in conflict with each other: the fact that there are grammaticalisation processes does not contradict the idea that constraints on such processes have evolved biologically. I will focus on grammaticalisation in a separate lecture in week 9.

In chapter 14, Fitch discusses his own account: musical protolanguage. I will discuss this briefly in the lecture, but the reading material is just the bit that discusses Wray’s holistic protolanguage, as this has been a major topic in the language evolution debate. Fitch’s text gives a concise summary of Wray’s work, and some of the criticism that it has received. In the tutorial, you will focus on this in more detail, and discuss Alison Wray’s and Maggie Tallerman’s papers.

References

Bidese, E., Padovan, A., and Tomaselli, A. (2012). Against protolanguage. In

L. McCrohon, T. Fujimura, K. Fujita, R. Martin, K. Okanoya, R. Suzuki,

and N. Yusa, editors, Five approaches to Language Evolution: proceedings

of the Workshops of the 9th International Conference on the Evolution of

Language.

L. McCrohon, T. Fujimura, K. Fujita, R. Martin, K. Okanoya, R. Suzuki,

and N. Yusa, editors, Five approaches to Language Evolution: proceedings

of the Workshops of the 9th International Conference on the Evolution of

Language.

Fitch, W. T. (2010). The Evolution of Language. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, K. (2010). Is a holistic protolanguage a plausible precursor to language?

A test case for modern evolutionary linguistics. In M. A. Arbib and D. Bickerton, editors, The emergence of protolanguage: holophrasis vs compositionality. John Benjamins.

A test case for modern evolutionary linguistics. In M. A. Arbib and D. Bickerton, editors, The emergence of protolanguage: holophrasis vs compositionality. John Benjamins.