For this lecture you will be reading Christiansen & Devlin (1997), henceforth C&D. In lecture 5 we moved from studying innate communication to learned communication: in this paper C&D use connectionist (neural network) models to show that languages differ in their learnability, and that that learnability of a language correlates with frequency in a cross-linguistic corpus: languages that are hard to learn (for a neural network) are rare (for humans). Much of the rest of this course will be based around this idea that there is a link between learning and the kinds of languages we see around us, so this paper forms an important first step along that road – we won’t be working with their model directly, but it is intended to get you thinking about how language learning might shape the kinds of languages we see in the world.

Some additional info on Simple Recurrent Networks

The paper should be understandable (I hope!) based on what you already know about neural networks in general, although the network that Christiansen & Devlin use is far more sophisticated than any of the ones we will be modelling in class. They use a Simple Recurrent Network (SRN), which is a standard connectionist paradigm for modelling sequence learning. SRNs can be used to learn all kinds of sequential information – they aren’t specialised in any sense for learning linguistic sequences per se. C&D are quite brief on how the SRN works, how it is trained etc in their paper, so I will provide a little more information here – this might make most sense if you read their paper up to the section titled “Simulations”, then read this quick explanation of SRNs, then duck back in to the paper. And don’t forget the quiz at the end.

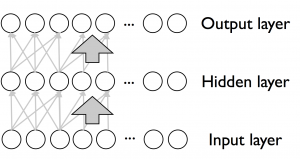

An SRN is a neural network that consists of 3 or more layers of units, with the units at one layer being connected to the units at the next layer. Activation flows from the input layer through the ‘hidden’ (i.e. not input or output) layer to the output layer. As in all neural networks, the way in which activation spreads is dependent on the strength of the connections, and learning is achieved by adjusting those connections to change the way that inputs map to outputs.

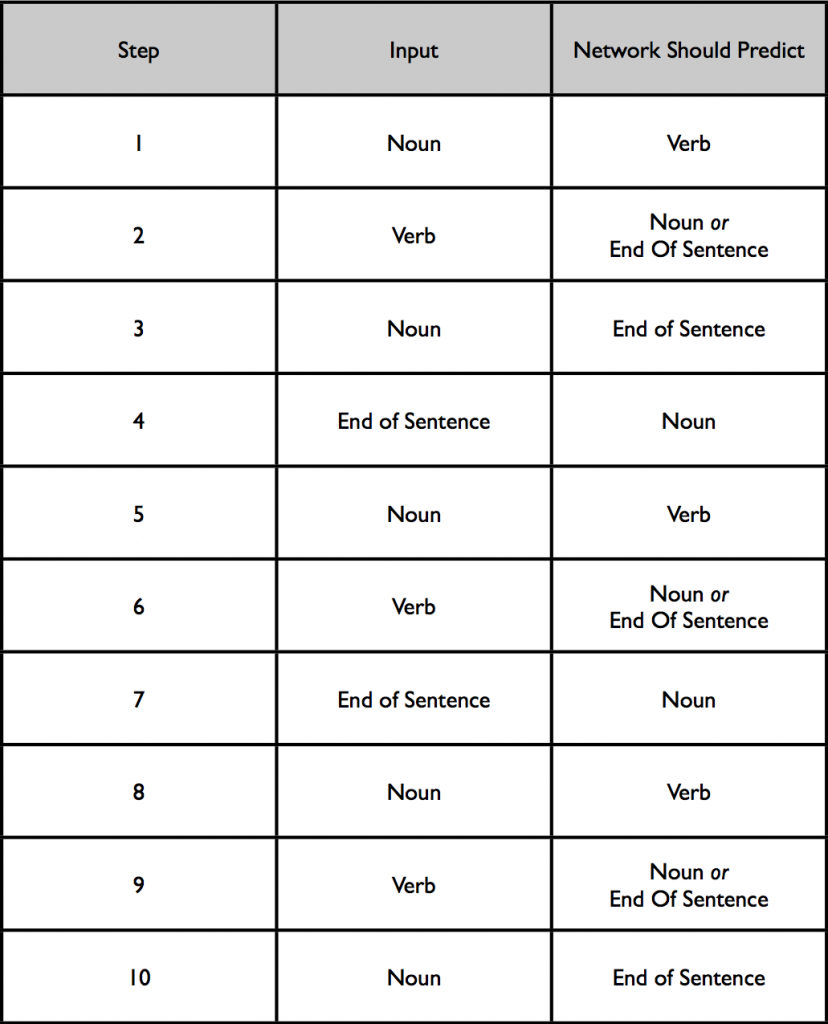

In C&D’s model, they are training the network to learn possible sequences of grammatical categories, corresponding to grammatical sequences in the language the network is trying to learn. The way they do this is by training the network to predict the next element in the sequence, based on the sequence so far. So, for instance, imagine a network learning a little simple grammar, a simplified version of one of the grammars C&D use: a sentence consists of a Noun, a Verb, and then optionally (say half the time) another Noun, with no agreement between subject and verb. In C&D’s terms, this language can be expressed by a single grammar rule: S->N V (N). The network is then trained on a corpus of sentences generated by this grammar. Imagine that this corpus consisted of just 3 sentences: N V N, N V, N V N. In this case, the network would be trained in the following way:

So in step 1, the network receives a Noun as input (because all sentences in our mini language start with a Noun), and it should predict that the next element in the sequence should be a Verb (because all sentences in our language contain a Noun and a Verb). Then in step 2 it receives the next element of this sentence, a Verb, and should predict that the 3rd element of the sequence will either be a Noun (for an NVN sentence) or the End of Sentence character (if it’s an NV sentence). In fact this sentence is NVN, so at step 3 the network receives a Noun as input: now it should confidently predict that the next element in the sequence will be End of Sentence, since that’s the only possibility in our target language once you have seen the sequence N V N. And so on.

As they mention in the paper, C&D’s network has 8 input units and 8 output units: there is one input unit to represent each syntactic category (singular N, plural N, singular V, plural V, singular genitive, plural genitive, adposition) and an additional unit to represent the End of Sentence marker. Similarly, each unit in the output layer is interpreted as representing a syntactic category or end of sentence marker. In order to present a singular Noun to the network, we activate the input unit corresponding to singular Noun. We then propagate that activation forward through the network to get a pattern of activation over the output units, which we interpret as the network’s prediction about the next element in the sequence. For example, at an early stage of learning the network might predict, based on an input singular Noun, that all possible outputs are equally possible next elements in the sequence – this is a bad prediction, because only certain items can follow a singular Noun, due to the constraints of the grammar.

Learning uses the error on these predictions – the difference between what the network predicted would come next and what actually could come next – to adjust connection weights. Specifically, learning involves adjusting connection weights in the network (using a gradient descent algorithm know as “backproagation of error” – you don’t need to know the details) so that its predictions improve – as the network learns, its predictions should get closer and closet to the truth, and when it has learnt well it should be predicting the next character in a sequence quite accurately. C&D measure how well the network is learning by computing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between what the network should have predicted and what it did predict: MSE will be high when the network is doing a bad job of predicting upcoming elements in the sequence, and low when it has learnt the statistical patterns in its input (‘learnt the grammar’, if you like), and is correctly able to predict the next element in the sequence.

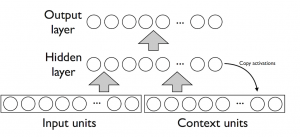

The network I just described to you is called a Feedforward Network – activation feeds forward from the input to the output. In order to get this network to learn sequences, you actually need a little bit more machinery – you have to give the network a ‘memory’ for items in the sequence so far. Returning to my toy S-> N V (N) grammar, what should you predict will follow a Noun? Well, that depends on what preceded the Noun – if it was the first Noun in the sentence, it must be followed by a Verb; if it was the second Noun in the sentence, it must be followed by an End of Sentence marker. A basic feedforward network doesn’t have this kind of memory, because it only sees the current input, and so can’t learn sequences – it could only learn that half the time Nouns are followed by Verbs and half the time by End of Sentence, since it can’t see that this is predicted by what came before the current input.

In order to permit sequence learning, you need to use a network which has a memory for previous elements in the sequence. C&D use the simplest such network, an SRN. An SRN has an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. But it has an additional context layer, which sits alongside the input layer and feeds into the hidden layer. At each time step, the activations from the hidden layer are copied to the context layer; therefore, the hidden unit activations when processing item n from a sequence can affect the hidden unit activations at element n+1 and therefore the output unit activations.

It turns out that this very simple sort of memory – the network ‘remembers’ its internal state (the activation of the hidden units) from one time step earlier, which in turn might reflect its internal state from two or more time steps previously – is enough to learn moderately fancy grammars. If you want to see how fancy, read Elman (1993).

About Christiansen & Devlin

I don’t know who Devlin is I’m afraid, but Morten Christiansen is a Prof at Cornell, using a bunch of experimental and computational (connectionist) techniques to understand linguistic and non-linguistic sequence learning. He actually did his PhD here in Edinburgh, in the Cognitive Science department, although that was before my time. He’s a well-known figure on the cognitive science and language evolution scene.

Post-reading quiz

You should do the post-reading quiz and compare your answers to mine.

References

Christiansen, M. H., & Devlin, J. T. (1997). Recursive inconsistencies are hard to learn: A connectionist perspective on universal word order correlations. In M. Shafto & P. Langley (Eds.), Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 113-118). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Elman, J.L. (1993). Learning and development in neural networks: The importance of starting small. Cognition, 48, 71-99.