Tuesday 1 December, 11:00–12:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Klaas Seinhorst, Amsterdam Center for Language and Communication, University of Amsterdam

Filling in the blanks – acquisition meets typology

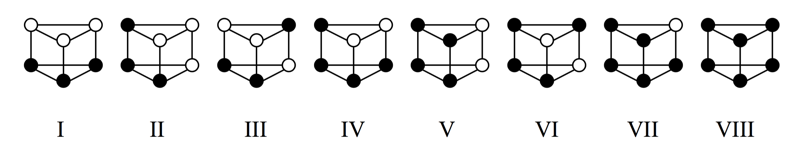

It has often been observed that languages disprefer gaps in their phoneme inventories: they tend to maximally combine their distinctive features. In the late 1960s, the French phonologist André Martinet suggested in passing that this tendency may be rooted in the acquisition process, but so far empirical evidence has mostly been lacking. I present exactly such evidence from experiments with human learners (n = 96), who were exposed to one of eight category structures. These category structures have one binary feature and one ternary feature: as such, they resemble plosive inventories from spoken language, which often have a binary voicing opposition ([±voice] or [±tense]) and a three-way place of articulation contrast (usually [labial] vs. [coronal] vs. [dorsal]).

Given these features, a type I language could have the plosives /p t k/; a type VIII language has either /p t k b d g/ (like English) or /p ph t th k kh/; a type VI language might have /b p d k/. Types I and VIII are predominantly found in the world’s languages.

The results of the experiments show that participants often regularise their input, i.e. they (quite literally) fill in the blanks: for instance, type VI is often classified as type VIII. Consequently, learners considerably reduce the cumulative complexity of the data set. These outcomes, then, seem to support two related hypotheses: (i) biases in pattern learning favour regular systems; (ii) the low degree of complexity that has been attested in spoken languages may be ascribed to the iterated effect of such biases.

Tuesday 24 November, 11:00–12:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Alan Nielsen

Systematicity, contrastiveness, and learnability: Evidence from a growing lexicon experiment

Typically, experiments exploring the degree to which systematicity and motivatedness compare the learnability of complete artificial lexica to one another, concluding that associations between words and meanings that are systematic create learnability penalties at certain sizes. That is, systematic associations between words and meanings, whether they are motivated or not, necessarily create artificial lexica that are more constrained, i.e. words are sufficiently similar to one another that they are easily confused.

In this talk I present the results of an experiment using a paradigm designed to explore this learning penalty directly by teaching participants an artificial language over time, allowing for a comparison between how well words are learned at first exposure, compared to how well they are learned after similar labels enter the lexicon.

Additionally, the experimental design allows for us to test a simple version of the bootstrapping hypothesis, which suggests that the acquisition of motivated tokens bootstraps the acquisition of later non-motivated tokens.

We find support for the first of these hypotheses: as signal spaces become increasingly saturated, individual labels within those lexica become increasingly difficult to learn. We do not, however, find support for the bootstrapping hypothesis.

Tuesday 27 October, 11:00–12:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Simon Kirby (work with Tessa Verhoef and Carol Padden, UCSD)

Naturalness and Systematicity: Evidence from artificial sign language

Language is shaped by cognitive biases. These biases can influence the emergence of linguistic structure through multiple linking mechanisms: improvisation of novel solutions to communicative tasks; repeated interaction between communicating individuals; and iterated learning of linguistic conventions over multiple generations. The study of language evolution seeks an explanation of the origin of linguistic structure in terms of these processes and their interaction with human cognition.

In this talk I will concentrate on two types of bias that shape the emergence of linguistic structure: naturalness, and systematicity. Both are the result of a domain general preference for simplicity, but differ in how this simplicity is realised. Naturalness is a property of the relationship between linguistic form and something non-linguistic, whereas systematicity is a property of the relationship among linguistic elements. I will argue that the former type of bias is felt most strongly during improvisation, whereas the latter is felt most strongly during learning.

To test this, we look at a formal feature that governs the lexicon of sign languages: the so-called instrument vs. handling distinction. This has been recently argued to exhibit “patterned iconicity”, a property that combines both naturalness and systematicity. We show in series of artificial sign language experiments online and in the lab that even participants who have never been exposed to sign languages are sensitive to this feature. We show a very strong naturalness bias for instrument forms to be matched with objects and handling forms to be matched with actions. However, the naturalness bias that favours an iconic relationship between form and meaning can be overturned after a small number of exposures to an anti-iconic artificial sign language. This shows that although naturalness may be important in the early stages of language emergence, it is systematicity that is the driving factor where sets items are being learned and transmitted.

NOTE UNUSUAL DAY AND TIME

Friday 23 October, 16:00–17:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Jelle Zuidema, Institute for Logic, Language and Computation, University of Amsterdam

Deep learning models of language processing and the evolution of syntax

Researchers that assume discrete, symbolic models of syntax, tend to reject gradualist accounts in favor of a ‘saltationist’ view, where the crucial machinery for learning and processing syntactic structure emerges in a single step (as a side-effect of known or unknown brain principles or as a macro-mutation). A key argument for the last position is that the vast amount of work on describing the syntax of different natural languages makes use of symbolic formalisms like minimalist grammar, HPSG, categorical grammar etc., and that it is difficult to imagine process of any sort that moves gradually from a state without to a state with their key components. The most often repeated version of this argument concerns ‘recursion’ or ‘merge’, which is said to be an all or nothing phenomenon where you can’t have just a little bit of it.

In my talk I will review this argument in the light of recent developments in computational linguistics where a class of models has become popular that we can call ‘vector grammars’, that include the Long-Short Term Memory networks, Gated Recurrent Networks and Recursive Neural Networks (e.g., Socher et al., 2010). These models have over the last two years swept to prominence in many areas of NLP and shown state of the art results on many benchmark tests including constituency parsing, dependency parsing, sentiment analysis and question classification. They have in common that they are much more expressive than older generation of connectionist models (roughly speaking, as expressive as grammar formalisms popular in theoretical linguistics), but replace the discrete categorical states from those formalisms with points in a continuously valued vector space and hence quite easily allow accounts of gradual emergence (as exploited when these models are trained on data using variants of backpropagation).

I will conclude that these new type of models, although mostly evaluated in a language engineering context, hold great promise for cognitive science and language evolution. For theories of the evolution of grammar and syntax they effectively undermine a key argument that the only explanatory models are incompatible with gradualist evolution; rather, they show that syntactic category membership, recursion, agreement, long-distance depencies, hierarchical structure etc. can all gradually emerge, both in learning and in evolution.

Tuesday 13th October, 11:00–12:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Language learning and word order regularities: Children’s errors reflect a typological preference for harmonic patterns

Much recent debate in cognitive science concerns whether language universals exist and whether there is a connection between language acquisition, language change, and linguistic typology. However, recent studies have made important progress on these questions by demonstrating, in at least a few cases, that laboratory learners alter artificial languages toward patterns that are common cross-linguistically. Here we ask whether child learners do this even more strongly than adults. We focus on a bias for harmonic word order patterns and show that the strength of this bias changes dramatically over age. This suggests an important role for children in language change and underscores the importance of including child learners in investigations of the cognitive underpinnings of biases shaping language.

NOTE UNUSUAL DAY, TIME, AND LOCATION

Friday 2nd October, 14:00–15:30

Informatics Forum, 4.31/4.33

Ted Gibson, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, MIT

Information theoretic approaches to language universals

Finding explanations for the observed variation in human languages is the primary goal of linguistics, and promises to shed light on the nature of human cognition. One particularly attractive set of explanations is functional in nature, holding that language universals are grounded in the known properties of human information processing. The idea is that grammars of languages have evolved so that language users can communicate using sentences that are relatively easy to produce and comprehend. In this talk, I summarize results from explorations into several linguistic domains, from an information-processing point of view.

First, we show that all the world’s languages that we can currently analyze minimize syntactic dependency lengths to some degree, as would be expected under information processing considerations. Next, we consider communication-based origins of lexicons and grammars of human languages. Chomsky has famously argued that this is a flawed hypothesis, because of the existence of such phenomena as ambiguity. Contrary to Chomsky, we show that ambiguity out of context is not only not a problem for an information-theoretic approach to language, it is a feature. Furthermore, word lengths are optimized on average according to predictability in context, as would be expected under and information theoretic analysis. Then we show that language comprehension appears to function as a noisy channel process, in line with communication theory. Given si, the intended sentence, and sp, the perceived sentence we propose that people maximize P(si | sp), which is equivalent to maximizing the product of the prior P(si) and the likely noise processes P(si → sp). We discuss how thinking of language as communication in this way can explain aspects of the origin of word order, most notably that most human languages are SOV with case-marking, or SVO without case-marking.

Tuesday 22nd September, 11:00–12:30

Room 1.17, DSB

Structural priming in an artificial language

I am going to talk about a study that used artificial language learning paradigms to investigate structural priming (coordination with the syntactic structure of the partner’s previous utterance) during communicative interaction. We trained participants on artificial languages exhibiting unpredictable variation in word order, and subsequently had them communicate using these artificial languages. We found evidence for structural priming in two different grammatical constructions and across human-human and human-computer interaction. Priming occurred regardless of behavioural convergence: communication led to shared word order use only in human-human interaction, but priming was observed in all conditions. Furthermore, interaction resulted in the reduction of unpredictable variation, both in human-human interaction and in a condition where participants believed they were interacting with a human but were in fact interacting with a computer, suggesting that participants’ belief about their communication partner influenced their language use.

LEC founder Prof. Jim Hurford has been elected to the British Academy, in recognition of his outstanding research. Congratulations Jim!

LEC founder Prof. Jim Hurford has been elected to the British Academy, in recognition of his outstanding research. Congratulations Jim!

Tuesday 9th June, Room 1.17, DSB, 11:05-12:30pm

Jon W. Carr

The emergence of categorical and compositional structure in an open-ended meaning space

Language facilitates the division of the world into discrete, arbitrary categories. This categorical structure reduces an intractable, infinite space of meanings to a tractable, finite set of categories. By sufficiently aligning on a particular system of meaning distinctions, two members of a population can rely on this shared categorical structure to successfully communicate. Language also makes use of compositional structure: the meaning of the whole is derived from the sum of its parts and the way in which those parts are combined. Compositional structure allows languages to be maximally expressive and maximally compressible. Although the emergence of each of these properties has previously been studied in isolation, we show that compositional structure can evolve where no categories have been defined in the meaning space by the experimenter (or, conversely, that categorical structure can evolve where no set of words has been defined in the signal space). We show this using the experimental paradigm of iterated learning using a meaning space that is open-ended.

The meaning space consisted of randomly generated triangle stimuli. The space is continuous and the dimensions of the space are not determined by the experimenter. In addition, the set of stimuli that participants are tested on changes at each generation, such that no two generations are ever exposed to the exact same stimulus. In our first experiment, categorical structure emerged to arbitrarily divide the space into a small number of categories. However, there was no evidence of compositional structure in this experiment. In two additional experiments, we added expressivity pressures: the first of these used an artificial pressure and the second used dyadic communication. Only in the experiment with communication did we find evidence of compositional structure, suggesting that communicative pressures are required for compositionality to arise under more complex, higher-dimensional meaning spaces.