We want you to read chapter 2 of Skyrms (2010) – I am skipping chapter 1 because it is rather technical and the core concepts are covered below, but if you really really want to read chapter 1 then you can.

Before you read Skyrms chapter 2, read the material below, then after you have done the reading take the short quiz (link at the bottom) – same idea as with the readings for lecture 1.

In this course we are going to be using simulation models to explore how processes of evolution and learning might shape a linguistic system. Language is a system for communication (depending on who you listen to, either primarily or at least sometimes), for conveying information about the state of the world (including our own internal states, i.e. knowledge, thoughts and feelings). We will spend the first half of the course considering how to model a really simple kind of communication system, often called a signalling system. In this online material I will explain (in fairly abstract terms) what a signalling game is, what a signalling system is, and then the Skyrms reading will cover some examples of signalling in nature.

Sender-receiver games

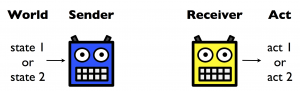

Skyrms takes as his starting point the signalling game introduced by Lewis (1969) – Skyrms calls these sender-receiver games rather than signalling games, for reasons that will become clear later. Imagine two individuals, situated in some world. The wold has one of two possible states, and one of our two individuals, the sender, knows what the state of the world is. The other individual, the receiver, can’t observe the state of the world themselves, but has two acts they can perform – these acts match up with states of the world, such that if the receiver performs act 1 when the world is in state 1 then both sender and receiver are rewarded, and similarly if the receiver performs act 2 when the world is in state 2, both sender and receiver are rewarded; otherwise (i.e. when the act and the state mismatch), neither receive a reward.

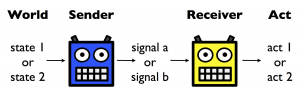

If this was all there was to the game, it would be kind of dull – the sender knows the state of the world but can’t act on it, the receiver can act on it but doesn’t know what state the world is in and can therefore do no better than guessing. Lewis’s signalling game, as the name suggests, adds signals to this simple picture: the sender can provide the receiver with a signal, drawn from some small set of possible signals (let’s imagine there are two signals, and call them signal a and signal b). The receiver can choose which act to perform based on the signal they get from the sender.

Crucially, if sender and receiver do the right thing, it’s now possible for them to always get the reward: they can arrange things such that the receiver always selects the appropriate act for the state of the world, based on the signal provided by the sender. Informally, we might say that communication takes place, if:

- the sender has some sensible strategy for selecting signals based on the state of the world, and

- the receiver has a strategy which allows them to selects an act in an appropriate way given that signal.

Think for a moment about what the best strategies are for sender and receiver. Is there a single best strategy for sender or receiver? Does the strategy used by the sender determine what the best strategy is for the receiver, or vice versa? Once you’ve had a bit of a think about it, read on.

[If the foregoing is too abstract for you, imagine a more concrete scenario. You are in a room with a friend and me, the experimenter. I hide a token under one of two cups (call them cup 1 and cup 2), in a way that it's visible to you but not to your friend (so the position of the token corresponds to the state of the world, visible only to the sender, you). I then ask your friend, the receiver, to select a cup (perform one of two acts): if they pick the cup with the token under it, then you both get £1; if they pick up the wrong cup you both get nothing (so the environment is set up such that the correct act in the correct world state generates a reward for sender and receiver). Finally, I give you, the sender, two cards with the letters "a" and "b" printed on them nice and clearly. You can communicate to the receiver using those cards but nothing else - you can hold up a card before they select a cup, but you can't do anything else (you can't say "left", or point left, or encourage them when they start heading left, etc). How would you solve this task if you and your friend had a chance to agree a strategy? How about if you weren't allowed to confer, and played the game only once? What do you think would happen if you played it repeatedly with the same partner?]

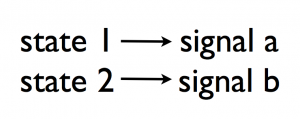

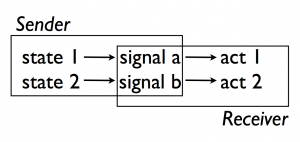

Here’s a possible sender strategy: If the world is in state 1, I send signal a. If the world is in state 2, I send signal b. I could write that same strategy more concisely, like this: state 1 -> signal a, state 2 -> signal b. Or I could write it even more concisely, like this: 1->a, 2->b. But initially I’ll give you a nice picture:

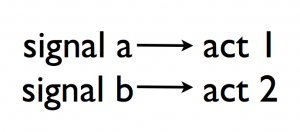

When will a sender who uses this strategy communicate reliably with the receiver? This of course depends on the strategy the receiver uses. In particular, if the receiver uses this strategy:

then the sender’s signal will always allow the receiver to select the correct act. Whenever the world is in state 1, the sender sends signal a, the receiver selects act 1 based on signal a, and both are rewarded; similarly, whenever the world is in state 2, the sender sends signal b, the receiver selects act 2 based on signal b, and both are rewarded.

So that looks like the combination of those two strategies is a good one – Skyrms calls this kind of pairing of a signalling and receiving strategy that guarantees the reward a signalling system, to convey the fact that the signals actually function as signals – they signal to the receiver which action should be taken.

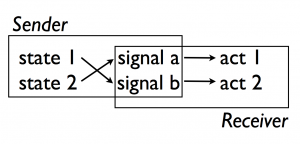

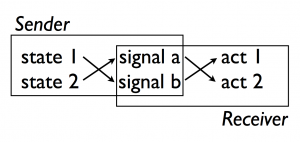

However, these two strategies are not always the right strategies to apply. Imagine our receiver applied the strategy given above. That’s the best possible strategy if the sender is using 1->a, 2->b, but it’s utterly disastrous if the sender is using the mirror-image strategy 1->b, 2->a:

Whenever the world is in state 1 the sender sends signal b, the receiver ‘misunderstands’ the signal as meaning they should play act 2, leading to a failure of communication and no reward. The same problem applies for state 1, and neither sender or receiver ever get rewarded. This is actually worse than if signals didn’t exist and the receiver just selected an act at random.

But there’s nothing inherently bad about the sender playing strategy 1->b, 2->a - there’s a matching receiver strategy (b->1, a->2) which is great for that sender strategy (but which would be disastrous if paired with other sender strategies).

In other words, the sender and receiver face a coordination problem: there is no single best way to signal, rather they have to coordinate the strategies they use in order to receive a reward, and failure to coordinate means no communication and no reward. Language (and basically all other communication systems, including the animal systems discussed by Skyrms in chapter 2) rely on populations solving this coordination problem. The question is, how do populations ‘agree’ on what conventions should be used? Understanding how this can happen is a fundamental question in understanding how natural communication systems can emerge, and therefore a fundamental component of understanding how a communication system like human language could evolve.

How are signalling systems established?

The first possibility, which we can rule out fairly quickly, is that sender and receiver explicitly agree on a signalling convention to apply, by discussing it in some explicit, meta-communicative fashion – “How about this: if the world is in state 1, I say a, if it’s in state 2, I say b, and you act accordingly?”. The reason we can rule this out is that it requires the existence of some kind of communicative medium which we can use to discuss how we should communicate – in other words, it presupposes the existence of the meta-communciation system that allows us to discuss how to signal. If we are interested in how communicative conventions are established in the first place, it would be sadly circular to say that they are established through the use of existing communicative conventions. That’s why I used ‘agree’ in scare quotes above – the agreement among senders and receivers is somehow implicit, and we are interested in how these implicit conventions might form.

Another possibility, which Skyrms discusses in Chapter 2, is that some combinations of state and signal are more natural than others – he calls this natural salience. For example, if you were playing the cup-and-token game I described above with another person, and the states were labelled 1 and 2, and the signals labelled a and b, I bet the ‘natural’ inclination for some people would be to use signal a for state 1 and signal b for state 2 – a is the first element in the alphabet and 1 is the first element in the number sequence (unless you are a dedicated Python programmer), so based on what you know about letters and numbers they go together quite well. Skyrms discusses other less artificial cases of natural salience in the reading, including e.g. the baring of teeth in dogs as a signal of aggression. Natural salience of this sort gives a convention a nudge in a certain direction, making it more likely or more sensible or more natural that certain states and certain signals will be paired together.

Natural salience might help a bit, but unless the salience relationship is extremely strong it’s unlikely to do the whole job, and in some cases (where there is no natural pairing of states and signals) it can’t help at all. For language, in particular, as pointed out by Saussure, linguistic signs are arbitrary (at least at a first approximation): for the vast majority of every language’s lexicon, there is no natural association between words and the meanings they convey. How can signalling systems be established in such cases, where they have to be purely conventional, i.e. not based on natural salience?

Skyrms points towards two possible mechanisms. We will consider these in detail in the upcoming readings, lectures and labs, but I will briefly outline them here so you can get a flavour of what is to come. Firstly, signalling systems could evolve under natural selection: if the signalling strategy an individual uses is coded in their genes and inherited by their offspring, and assuming coordination yields a reward for sender and receiver, over many many generations sender and receiver strategies might adapt to one another, leading to optimal, innate, ‘instinctive’ sending and receiving behaviours. As a secondly possibility, learning might have something to do with it: sender and receiver might adjust their strategies as a result of some element of their experience, and this might somehow lead to signalling systems developing. Skyrms is particularly keen on reinforcement learning (individuals adjust their behaviour based on the presence or absence of reward), but we will pursue a slightly different route, focussing instead on observational learning (you observe how other individuals signal, and base your own signalling behaviour on those observations). But that is all to come later in the course.

A few quick asides

A few additional comments:

This is a very simple model of language and communication – we are going to start simple, and build towards more complex language-like phenomena. Starting simple is generally a good idea in models. But also, there are interesting parallels between these signalling games and important cases of signalling in the natural kingdom, including in other primates. Have a think about what is missing from the signalling game as a model of human language, make a wish list, then towards the end of the course we can see how far we got in modelling these things and ticking them off your list.

I am going to be quite free with my description of what is involved in signalling, and talk freely about sender and receiver strategies, senders selecting signals in order to communicate, signals having meaning, etc. That’s because I am primarily interested in language, and I don’t have a problem imagining that humans do all of these cognition-heavy, maybe even intentional actions when communicating. But Skyrms is at pains to point out that a rich internal mental life is not required for signalling – he discusses examples of signalling in bacteria, which I don’t think do cognition (certainly not in the same way that humans do). That’s worth bearing in mind if you find yourself getting irritated that I talk about the meaning a monkey intends to convey with a signal, or something like that – it would be possible to rephrase that statement in far less mentalistic language.

OK, so on to Skyrms Chapter 2

Brian Skyrms is a philosopher who is interested in the evolution of social conventions, including (but not exclusively) the conventions involved in signalling. His 2010 book is a fairly wide-ranging investigation of the emergence of signalling, touching on a number of topics that we will cover in this course, including learning, evolution, issues of altruism and honesty, and complex signals. He employs a variety of models to explore these questions, mixing mathematical and computational models, although the book itself is fairly light on technical detail. It also goes very far very fast, which is one of the reasons why I haven’t set the entire thing as required reading.

Chapter 2, which I have set as reading, is a non-technical introduction to animal signalling, drawing parallels between alarm calling behaviour and the sender-receiver formalism described above, and then covering various interesting real-world extensions (eavesdropping, “syntax” in chickadee calls, displacement in the waggle dance of bees, and signalling in bacteria). When you get to the bit about alarm calling in vervets, you should check out this lovely youtube video featuring Robert Seyfarth talking about vervet alarm calls; when you get to the bit about bee dance, I’d recommend watching this extremely clear description of how the waggle dance works, and how von Frisch figured it out (plus it has some photos of von Frisch in lederhosen, which are worth a look).

Post-reading Questions

Once you have read this page and done the Skyrms reading, take this short quiz, which tests you on a few basics (so I can see if you understood the readings!) and gives you a chance to flag up things you want me to go over again in class (or it does if you do it the day before class!). Then you can compare what you said to my comments on how I would have answered.

References

Lewis, D. K. (1969). Convention. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Skyrms, B. (2010). Signals: Evolution, Learning, and Information. Oxford: Oxford University Press.