We want you to read chapters 1 and 2 of Sigmund (1995). But before you do, read the material below, and think about how you would answer the questions we pose. Then after you have done the reading take the short quiz (link at the bottom), which will give me some idea of how you got on with the reading and which also gives you the opportunity to tell me things you didn’t understand and would like clarified in class.

In this course we are going to be using simulation models to explore how processes of evolution and learning might shape a linguistic system. The aim of the first few lectures is to explain what that sentence means. What is a model? What is a simulation model? How can you build a model of a linguistic system? Then in later lectures we’ll go on to harder stuff: How can you model evolution? How can you model learning? But the starting point is to understand models: what they are, and what you can use them for.

What is a model?

A model is a miniature version of the system you are interested in. Models are typically much simpler than the system you are interested in, because that makes them easier to build, easier to play with, and ultimately easier to understand.

We will be building models of language, evolution and learning, but people use models in all kinds of domains. One of my favourite kinds of model (just because they are pretty) are wave models – here’s a video of a beautifully simple model wave in a tank.

Notice a couple of features of the model.

Firstly, it’s small and simple. It’s on a much smaller scale than the waves you get in the North Sea. The model sea bed is really simple (smooth surfaces, nice steady slopes – no shingle, no shipwrecks, no complex coastlines). And the water itself is even very simple - I bet it’s all approximately the same temperature, unlike the real sea, which is warmer near the surface.

Secondly, the model gives the guy with the microphone amazing control. If he wants to look at choppy waves, he turns the dial one way. If he wants to look at gentle waves, he uses another setting. The real world doesn’t work like that, and some events he might be interested in (e.g. really steep waves) might be very unpredictable or very rare, which makes them hard to study.

Thirdly, he can get a really really good look at what is going on inside the waves – he can easily observe stuff (like what the water is doing inside each wave, or the shape of the waves as they shoal) that would be much harder to do in the real world. He could, if he wanted, easily measure all these properties in his model system, which would be hard in the wild.

So he gains a lot by having this model of a wave. Have a think about what he loses by working with this model, rather than real waves, and we can discuss it in class.

Sadly, we aren’t going to be using wave models, because 1) they look kind of expensive and 2) this is a course about language, not waves. We also aren’t going to be using physical models, because they really aren’t that suitable to the kinds of things we want to model. Instead, we are going to be using computer simulations. This OK short video on how wave modelling might save people’s lives shows a mix of physical models and computer models to answer different questions. With the physical model they seem to be asking “how badly messed up will this wall get if we fire a telegraph pole at it?”. And in the computer simulation (which you can see in the little graphical animation of the tsunami), they want to ask “how many people might have died if they had gone upstairs rather than inland?”.

The idea behind computer models is the same as for physical models: we want a simple version of the system of interest, that is like it in important respects, that we have a high degree of control over, and that makes it really easy to measure the things we care about. However, building a computer model involves a different kind of work than building a physical model. The wave tank model is essentially the real thing in miniature: it’s a small amount of water sloshing about in a tank. And it works in the same way as the real thing because the laws of physics are the same as for the real thing – all we have to do is make a nice perspex tank, put some water in it and we have a wave model (more or less), since the world takes care of all the complex stuff for us, like how water molecules move, how they bump into each other, how they react when they hit a slope or a barrier, etc.

In contrast, in a computer model, we have to tell the computer how to work out all those things. In the wave model they show in the tsunami wave video, someone will have written a computer program which describes how water moves. This will be a simplified description: rather than describing what all the individual water molecules do at any point in time, it’ll have some general principles built in to it, like “water flows downwards”, “water flows round hard obstacles and can smash lighter ones”, etc (those descriptions won’t be informal English descriptions like that, of course, but really precise descriptions written in a language the computer can work with). But once that description is written in enough detail, the computer can work out what will happen from any given position: so you tell the computer “OK, start with a huge wave 1 mile offshore, and see what happens if water does what water does”, then the computer just mechanically follows the description it has been given and works out where the water will be after 1 minute, 2 minutes, 3 minutes, etc.

Have a little think about what kind of stuff you would include in a computer model of a wave if you were building it, and what kind of stuff you would leave out. Is everything important? Are the same things always important no matter what you want to use the model for?

We will be building and working with computer models in this class. We will be working with computer programs which specify how (simple!) languages work and how the processes we are interested in (e.g. evolution, learning) work, we will specify some starting conditions, and then we will have the computer run from there and figure out what happens over time, according to our rules.

What is a model for?

There are two main ways you can use a model: to work out in a very precise way the predictions of a theory, or to understand how a real-world system works by understanding how a model version works. These two approaches are related, and differ mainly in emphasis I think.

The tsunami wave video contains a (slightly macabre) example of prediction-testing using a model. One of the researchers had a theory that (counterfactually) if people had gone upstairs rather than inland when the tsunami struck, there might have been less deaths. This is hard to test in real life – how on earth would you do it? But it’s easy in the model. You add little simulated people to the model: again, they are probably really simplified model people, since all the model needs to know is where they start, how fast they move and in what direction, and how likely they are to die when they come into contact with water. Then you try running two versions of the model. In one version, the model people move inland as fast as they can. In the other, they move upstairs as fast as they can. You run both models a bunch of times, and see which version leads to fewer deaths (under the various assumptions you made when you were building the model). So you take your theory, instantiate it in a model (or in this case, two variants of the same model), then run the model to generate predictions.

Let’s imagine a different example, that actually relates to language rather than water. Suppose you have a really complex theory, say that specifies how linguistic variants diffuse over a social network. You think your theory makes a certain prediction, say that some sound changes are possible but others are impossible, or that some social groups will always lead changes whereas others will follow. It would be nice to look at real world language change and see if it matches this prediction, but first we better check exactly what our theory actually predicts – it would be embarrassing if we thought we understood the predictions of our theory but in fact made a mistake.

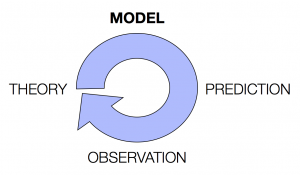

One way to see what a theory predicts is just think about it really carefully, check you think it makes sense, and then try to describe to other people why it makes sense. That might convince you, but it’s unlikely to convince a sceptic – what if they just disagree with your intuitions about how things will work out? Instead of building a verbal model or running a thought experiment, a computer modeller would build a computational model of the theory: they would turn the theory into a formal description that a computer could use (so they would tell the computer: variants spread like this but not like that, social networks look like this, let’s start with a social network where the variant is here and everyone else sounds like this, etc), then they would have the computer run the model. The computer slavishly follows the description that the modeller put in, which is based as faithfully as possible on the theory, and the modeller watches to see what happens – does the mechanically-derived series of events match her verbal prediction? If so, congratulations – you are very clever. But if not, why not? Is there something important missing from the theory, and therefore from the model? Is there something weird about the way the model was built, that isn’t actually faithful to the theory? Either way, the predictions of the theory are now nice and clear – a critic might argue that the model doesn’t really match the theory, but they can’t argue with the mechanically-derived predictions that the model produces, because the computer isn’t relying on imagination or intuition to figure out what happens next. The computer just slavishly following the rules, following what the theory says. Then once we have this nice precise, defensible set of predictions, we can go to the real world and see if things really work out in the same way as our theory (via the model) predicts. If they do, hurrah. If they don’t, maybe we can go back to our theory, tweak it some, tweak the model, and go round the whole cycle again.

One way to see what a theory predicts is just think about it really carefully, check you think it makes sense, and then try to describe to other people why it makes sense. That might convince you, but it’s unlikely to convince a sceptic – what if they just disagree with your intuitions about how things will work out? Instead of building a verbal model or running a thought experiment, a computer modeller would build a computational model of the theory: they would turn the theory into a formal description that a computer could use (so they would tell the computer: variants spread like this but not like that, social networks look like this, let’s start with a social network where the variant is here and everyone else sounds like this, etc), then they would have the computer run the model. The computer slavishly follows the description that the modeller put in, which is based as faithfully as possible on the theory, and the modeller watches to see what happens – does the mechanically-derived series of events match her verbal prediction? If so, congratulations – you are very clever. But if not, why not? Is there something important missing from the theory, and therefore from the model? Is there something weird about the way the model was built, that isn’t actually faithful to the theory? Either way, the predictions of the theory are now nice and clear – a critic might argue that the model doesn’t really match the theory, but they can’t argue with the mechanically-derived predictions that the model produces, because the computer isn’t relying on imagination or intuition to figure out what happens next. The computer just slavishly following the rules, following what the theory says. Then once we have this nice precise, defensible set of predictions, we can go to the real world and see if things really work out in the same way as our theory (via the model) predicts. If they do, hurrah. If they don’t, maybe we can go back to our theory, tweak it some, tweak the model, and go round the whole cycle again.

That’s how you might use a model to link theory to predictions. Another way of thinking about models (which I am keen on, and which Sigmund advocates in the reading) is that building models and playing with them can give you important insights into the real world: by understanding the processes in the model, you can understand the real thing. As I discussed with the wave machine, models make it easy to play with a system – you can turn the dials in different ways, and see what happens. As the tsunami example shows, you can easily try out counterfactuals, or add extra ingredients to the system (what if there was an early warning system? what if there were water breaks over here instead of where they actually were? what happens if a tsunami hits a bottle-shaped valley, or a wide bay, or a steep cliff?). Some of this might be very focussed, hypothesis-driven probing of the model. But some of it might be purely speculative – let’s try this and see what happens, I wonder what would happen if we did that. This kind of model play might not link directly to the real world, but it might never the less be useful: if it gives you, the modeller, a better feeling for how the model system can work, maybe you will start to get some useful insights into how things work in the real world.

That might sound much vaguer than the theory-model-predicition cycle I mentioned first, and it is! We will be doing lots of playing with models on this course, and maybe a bit of theory-testing – keep that contrast on a mental back-burner, and at the end of the course, decide for yourself which approach you think is most productive.

A quick word on mathematical modelling

All of the above referred to physical models and computational models, or simulation models. Probably the main technique actually used in the sciences is mathematical modelling – same idea as simulation modelling, but rather than writing down a computer program to build your model, you write down some equations, and then work out the predictions of the model using fancy maths. We won’t be doing any of that in this course, because I’m not a mathematician, and probably neither are most of you. You might occasionally catch sight of a few equations though – the key thing is not to panic. Often people describe computational models using little bits of maths (because it’s nice and concise and precise) – in most of the papers we will be looking at, this doesn’t happen much, or if it does the maths will be explained in words as well. Later on in the course we’ll look at a couple of equations ourselves, but only really simple ones involving multiplication and division. And all our models will be done in simulation on computers – you won’t be proving theorems, just hitting “play” on the computer and letting it take the strain.

What is the reading about?

Karl Sigmund is a mathematician who is interested in evolution: he builds mathematical models of evolution. This book is an introduction to the kind of work he does, talking about how mathematical models can help you understand various evolutionary processes (e.g. the evolution of sex ratios, or the evolution of cooperation). Like I just said, we aren’t actually going to be doing any maths in this course, but I have set this reading for two reasons. Firstly, in Chapter 1, Sigmund talks about gaining insights into complex real-world phenomena by playing with simple models – that’s what we’ll be doing in this course. Then in Chapter 2 he describes a really simple model of life, called Life, which nicely illustrates a couple of features that all good models have in common. In particular, Life is incredibly simple – just two rules – but generates some really complex and interesting behaviours.

If you find Life a bit dry based on Sigmund’s description of it, then you can read a recent Guardian article on it. And you should absolutely play with it yourself – you can use that online simulator to test out some of the patterns Sigmund talks about, or just start from a random set of cells and see what happens. And there are tons of great videos of complex Life stuff online – personally I like this really dramatic one.

Post-reading Questions

Once you have read this page and done the Sigmund reading, take this short quiz, which tests you on a few basics (so I can see if you understood the readings!) and gives you a chance to flag up things you want me to go over again in class (or it does if you do it the day before class!). Once you’ve done the quiz you can look at my comments on how I would have answered.

References

Sigmund, K. (1995). Games of Life: Exporations in Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour. London: Penguin